‘Every Story That We Covered Was A Test’: James Critchlow on the Creation of Radio Liberty

This year marks the 65th anniversary of RFE/RL’s Russian Service, known to audiences throughout Russia and the former Soviet Union as Radio Liberty (RL, in Russian Radio Svoboda). RL began broadcasting from Munich as “Radio Liberation” on March 1, 1953. Over the next year and a half, RL added Ukrainian, Belarusian, and 15 other local languages of the Soviet Union to its broadcasting repertoire, to provide balanced news and information to a diverse audience that was otherwise restricted to state-controlled media under the Soviet government’s strict censorship regime.

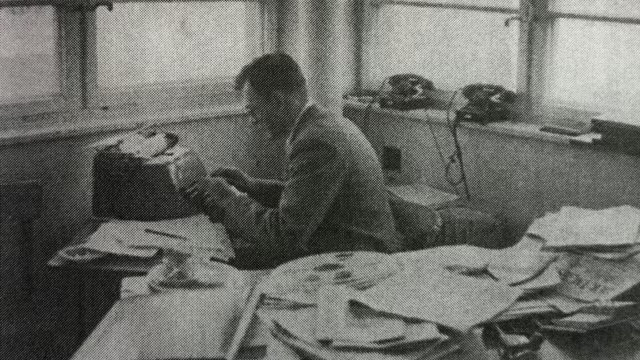

RFE/RL Pressroom spoke with James Critchlow, an American Russia specialist who helped establish RL, about those heady, early days in Munich.

RFE/RL Pressroom: Radio Liberty experienced a baptism by fire, having to prove its professionalism and journalistic integrity right out of the gate when a major international event—the death of Joseph Stalin—broke just days after RL began broadcasting. How did it fare?

James Critchlow: We had a total of five days of broadcasting experience when this story hit, and our technical setup was still very primitive.

We weren’t directly connected to the transmitters, so we had somebody on a motorcycle who would pick up the tapes of the broadcasts at the studio in Munich, then hand them off to the conductor of a train bound for Mannheim — our only transmitters were located near that city. So, the time between when you recorded the broadcast and when it actually went on the air could be anywhere from five or more hours.

When Stalin died, somebody got me out of bed at two o’clock in the morning and we rode up the autobahn to Mannheim. We set it up so that the broadcasters could dictate the programs to us over the phone and we could put them on the air immediately.

Our transmitters were not very powerful in those days and we had no way of knowing how many people were listening, but one interesting sign was that within minutes of our first broadcasts, the Soviet jamming took effect.

Pressroom: In your book, Radio Hole-In-The-Head/Radio Liberty, you emphasize the critical role played by the Russian-American diaspora and Soviet exile community in ensuring that RL would not become an anti-communist propaganda tool, but rather a professional media organization. How did they do this? What were some stories that tested RL’s ability to hold an unbiased editorial line?

Critchlow: Practically every story that we covered was a test. You have to remember that our mentality as Americans at this time was heavily influenced by the success of advertising in American life and the feeling you always had to exaggerate the things you wanted to emphasize and soft pedal the other ones. We realized that if you didn’t have credibility, nobody would listen — and the only way to have credibility was to tell all sides of the story, which is what we always tried to do.

We also had the dilemma of how to deal with the news when so many people’s emotions were involved with the subject matter. Eventually we succeeded in doing that. Remember, many of our broadcasters had directly suffered from Stalin’s crimes and they were not eager to talk dispassionately about these matters. But we succeeded in getting a balanced broadcast on the air, so people could believe what we were saying.

Pressroom: Broadcasting to the Soviet Union presented unique challenges beyond those faced by Radio Free Europe in Eastern Europe. It wasn’t just a question of creating programing in Russian and other indigenous languages. The Soviet listener was fundamentally different from an Eastern European listener. How did you see these differences manifest themselves?

Critchlow: The political situations in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe were so different at that time. In Eastern Europe you had countries which had been subjugated by the Russians, while in the Soviet Union you had people who had fought patriotically to overcome a Nazi invasion, and the outlook of people in that country was quite different. There is also the fact that people in Eastern Europe had only been exposed to Communism for a relatively brief time, whereas in the Soviet Union they’d been under Communism for 35 years or more and that was the only system they knew. There was a big psychological gap, I would say, between Eastern European audiences and Soviet audiences.

RFE/RL Pressroom: You admit to having underestimated the importance of other local languages in the Soviet Union, and like many others at RL, thought the project of Russification was already so far advanced that it was a mistake to allocate scarce resources to these languages when everyone spoke Russian anyway. What changed your mind?

Critchlow: At that time, everyone at the U.S. State Department on down to university specialists felt that it was just a matter of time before the Soviet Union became totally Russified and everyone would be speaking the same language and would share a common outlook as Soviet citizens, and that ethnic nationalism would be dead.

When I was stationed in Paris as the RL bureau chief, I met a man who had spent a lot of time in Uzbekistan who was convinced the Uzbek elites were gaining strength. This piqued my interest, and I began learning the Uzbek language and subscribing to Uzbek newspapers. At one point I came to the U.S. to present my findings on Uzbek nationalism to a group of experts who nearly laughed me off the stage. But as we now know, ethnic nationalism within the Soviet Union was always a powerful force.

RFE/RL Pressroom: With no access to the country, audience research was an extremely tricky business back then. You were involved with a team that developed a first-of-its-kind research methodology of interviewing Soviet citizens while they were abroad to find out who was listening to RL. How did this work?

Critchlow: We got some help from the American academic world, from mathematicians and political scientists at MIT and Harvard who designed a computer simulation that could take the fragmentary information we got from interviewing Soviet citizens traveling outside the country to try to estimate the number of people listening to different radio stations. Some thought our methods were unorthodox, but after the collapse of the Soviet Union we were able to gain access to the listenership studies done by the Soviet authorities during the same period and the results were similar.

— Emily Thompson

RFE/RL’s Russian Service is a multi-platform alternative to Russian state-controlled media, providing audiences in the Russian Federation with informed and accurate news, analysis, and opinion. Radio Liberty reached nearly 4 million Russians every week in fiscal year 2018. In the first half of 2018, Radio Svoboda’s website svoboda.org received an average 8.4 million visits every month. The Service has over 600,000 followers on Facebook, where its videos were viewed almost 47 million times in 2017; its videos were viewed 85.7 million times on YouTube.