Our History

For 75 years, RFE/RL has served as a beacon of hope, leading audiences out of information darkness.

Reaching Behind the Iron Curtain

Radio Free Europe (RFE) and Radio Liberty (RL) were created to serve as surrogate broadcasters providing trustworthy, locally relevant news, analysis and cultural programming to audiences behind the Iron Curtain. Truman Administration officials thought the United States could leverage the expertise of Soviet and Eastern European emigres to broadcast independent news in local languages to counter state propaganda. Both outlets grew, evolved, and consolidated in the 1970s, but our mission remains timeless. Today’s RFE/RL builds on this proud legacy.

1950s

Founded in 1950, RFE initially broadcast to Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland, and Romania. In 1953, RL began broadcasting to the Soviet Union in Russian and 17 other national languages.

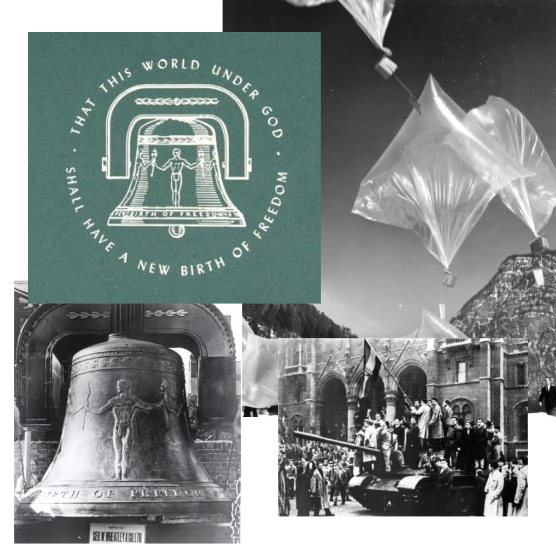

Initially, RFE and RL were funded principally by the U.S. Congress through the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). RFE also received supplemental private donations through the “Crusade for Freedom.”

RFE and RL provided what came to be known as “surrogate” broadcasting, an unbiased, professional substitute for the free media that countries behind the Iron Curtain lacked. The Radios — as they were colloquially called — produced programs focused on local news not covered in the state-controlled media, as well as religion, science, sports, literature, and music. The programs were produced primarily at the radios’ Munich headquarters and broadcast on shortwave and medium wave transmitters from Germany, Spain, Portugal, and, until the early 1970s, Taiwan.

1960s

Former RFE Director A. Ross Johnson in his account, No One is Afraid to Talk to Us Anymore: Radio Free Europe in 1989, writes that “by the end of the 1960s RFE/RL had become a seasoned substitute for national radios, commonly called surrogate broadcasters, focused primarily not on the United States or international issues … but on developments in the countries to which they broadcast. Their mission was to provide their listeners with a link to the West, to keep the hope of freedom alive, and to promote evolutionary change toward what after 1989 would be called a Europe whole and free.”

1970s

In 1971, all CIA involvement in RFE and RL ended. RFE and RL were funded by a public congressional appropriation through the Board for International Broadcasting and, after 1995, the Broadcasting Board of Governors (U.S. Agency for Global Media).

Emboldened by the Helsinki Final Act of 1975, increasing numbers of dissidents and other regime opponents began to challenge the communist system. As the leading international broadcaster in countries behind the Iron Curtain, RFE and RL provided a “megaphone” through which independent figures could reach millions of their compatriots with uncensored writings.

In 1976, RFE and RL merged into Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL), as we know it today.

1980s

In 1981, a terrorist bomb paid for by Romanian security services exploded at RFE/RL’s headquarters in Munich, injuring six and causing one million dollars in damage to the building.

With the collapse of communism on the horizon, some thought RFE/RL had fulfilled its mission and could be disbanded. But officials throughout Europe and Russia saw a continuing need for the kind of objective broadcasts that RFE/RL provided during times of democratic transition.

Beginning in 1989, RFE/RL established local bureaus throughout its coverage area to support the newly independent states as they grappled with the challenges of building new democracies. RFE/RL journalists helped train a new generation of local journalists by modeling journalistic ethics of fairness and factual accuracy.

1990s

During the failed Soviet putsch of 1991, RFE/RL’s Russian Service was one of the few sources of reliable information. As a result of its dramatic broadcasts, the Service finally received official accreditation in Russia. In August 1991, President Boris Yeltsin signed a decree permitting RFE/RL to open a bureau in Moscow.

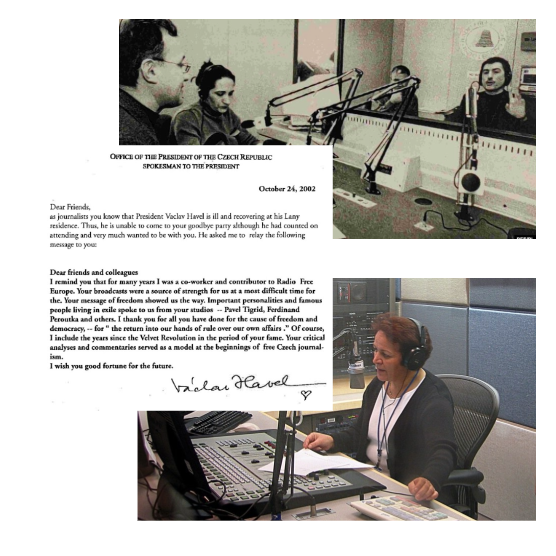

Facing massive post-Cold War funding cuts that precluded continued operations in Germany, RFE/RL accepted the invitation of Czech President Vaclav Havel and Prime Minister Vaclav Klaus and relocated its broadcasting center to Prague in 1995.

After the end of the Cold War, RFE/RL responded to emerging threats to democracy and media freedom by launching several new language services. Following the violent breakup of Yugoslavia, RFE/RL began broadcasting in Serbian, Croatian, and Bosnian to the Yugoslav successor states in early 1994, in Albanian to Kosovo in 1999, and in Macedonian and Albanian to Macedonia in 2001.

As countries established democratic governments and started to join NATO and the European Union, RFE/RL concluded that it had fulfilled its mission in several markets. The Hungarian Service was closed in 1993, the Polish Service in 1997, and Czech broadcasts ended in 2002.

2000s

Russia’s armed aggression and increased use of disinformation as a weapon during the early 2000s led RFE/RL to create the Russian language program Ekho Kavkaza (to serve audiences in Abkhazia and South Ossetia after Russia’s 2008 invasion of Georgia).

Broadcasts in Estonian, Latvian, Lithuanian, Slovak and Bulgarian ceased in 2004, and RFE/RL’s broadcasts to Romania ended in 2008.

Reflecting rising American attention to the Middle East, RFE/RL began broadcasting in Arabic to Iraq and in Persian to Iran in 1998; after 2002 the broadcasts to Iran continued as Radio Farda.

In 2002, RFE/RL resumed broadcasts in Dari and Pashto to Afghanistan that had ended in 1993 after the Soviet Union’s military withdrawal. The same year, RFE/RL reestablished broadcasts in three languages of the North Caucasus region of Russia.

2010s

In 2010, to provide an alternative to burgeoning Islamic extremism, RFE/RL began broadcasting in Pashto to northwestern Pakistan and the Afghanistan-Pakistan border region. In 2015, RFE/RL’s Iraq broadcasts merged with MBN’s Radio Sawa.

Following Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea, RFE/RL’s Ukrainian Service launched the tri-lingual Crimea.Realities and Russian-language Donbas.Realities. In 2014, RFE/RL also launched a Russian-language digital news network under the “Current Time” brand, in cooperation with Voice of America. Current Time grew quickly, from a 30-minute daily news show, into a 24/7 digital television channel.

As part of a comprehensive approach to Russian disinformation, RFE/RL expanded local news coverage between 2016–2019 by creating Russian-language websites serving audiences in Russia’s North Caucasus, Middle Volga, Siberian, and Northwestern territories.

Starting in December 2017, Russia’s Ministry of Justice declared RFE/RL and nine of its Russian-language reporting projects “foreign mass media performing the functions of a foreign agent” and has since named over 40 RFE/RL journalists as individual “foreign agents.”

In 2019, RFE/RL returned to Romania and Bulgaria, amid growing concern about a reversal in democratic gains in the two countries. RFE/RL also resumed content production in Hungary in September 2020.

2020–Present

As the COVID-19 pandemic wreaked havoc across RFE/RL’s coverage area, audiences turned to RFE/RL for accurate information about the pandemic.

In August 2021, the withdrawal of U.S. forces and subsequent takeover by the Taliban in Afghanistan forced RFE/RL to close its bureau in Kabul and evacuate hundreds of Radio Azadi journalists and their family members. Radio Azadi has since reshaped its programming to reflect the loss of its radio distribution network and respond to the needs of Afghan citizens.

In March 2022, Russian authorities began bankruptcy proceedings against RFE/RL forcing the company to suspend operations in Moscow and move its Russian Service and Current Time journalists to Riga, Latvia, for their safety.

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 marked a significant turning point for RFE/RL, as RFE/RL journalists and staff intensified on-the-ground reporting efforts to cover the brutal combat in eastern Ukraine—documenting Russian atrocities and alleged war crimes against the Ukrainian people in locations such as Bucha and Izyum, the environmental devastation caused by the invasion, and the plight of millions of displaced Ukrainians. In February 2024, Russia labeled RFE/RL, an “undesirable organization.”

Since 2022, RFE/RL’s Persian-language Service, Radio Farda, has rapidly expanded its programming, reaching audiences inside and outside of Iran with unbiased reports, analysis, and cultural content across platforms. Radio Farda published exclusive interviews with family members of young victims killed in the 2022 nationwide protests against mandatory hijab enforcement – Mahsa Amini, Nika Shakarami, and Hadis Najafi.

In October 2023, RFE/RL journalist and American citizen Alsu Kurmasheva was wrongfully detained by Russian authorities in Kazan. Her detention garnered widespread attention worldwide as she was charged under Russia’s controversial “foreign agent” law. She remained detained for nine months until a prisoner exchange in August 2024.

Two RFE/RL journalists remain unjustly imprisoned: Farid Mehralizada (Azerbaijan) and Nika Novak (Russia).

In November 2025, RFE/RL’s Hungarian Service, known locally as Szabad Európa, ceased operations as directed by the United States Agency for Global Media (USAGM). The Service had relaunched in September 2020 at the direction of the U.S. Congress.

Despite challenges presented by expanding authoritarian regimes and new censorship technologies, RFE/RL is one of the most comprehensive media organizations in the world, producing digital, television, and radio programs in countries where a free press is either banned by authoritarian governments or not fully established.

Additional Resources

Learn about the early years of RFE and RL in Arch Puddington’s “Broadcasting Freedom: The Cold War Triumph of Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty,” A. Ross Johnson’s “Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty: The CIA Years and Beyond,” Allan Michie’s “Voices Through the Iron Curtain: The Radio Free Europe Story,” and Sig Mickelson’s “America’s Other Voice: The Story of Radio Free Europe & Radio Liberty.”

The Crusade for Freedom – the Free Europe Committee’s project to raise Americans’ awareness of, and funds for, Radio Free Europe – is examined in Richard Cummings’ “Radio Free Europe’s “Crusade for Freedom”: Rallying Americans Behind Cold War Broadcasting, 1950-1960.”

The Crusade for Freedom and its successor, the Radio Free Europe Fund, as well as the Radio Liberty Committee, produced several films and public service announcements during the 1950s and 1960s that promoted the work of RFE and RL, including “This is Radio Free Europe,” “This is Radio Liberty,” “Window to the West,” and “The Most Incredible Challenge”.

Mark Pomar provides a look at RFE/RL and Voice of America broadcasting efforts to Russia during the 1980s and early 1990s in “Cold War Radio: The Russian Broadcasts of the Voice of America and Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.”

The efforts by Poland’s Communist government to counter the impact of RFE’s influential Polish Service broadcasts are examined in Pawel Machcewicz’s “Poland’s War on Radio Free Europe. 1950-1989”

Several RFE/RL veterans have written personal accounts of their service with the Radios, including George Urban (“Radio Free Europe & the Pursuit of Democracy: My War within the Cold War”), Gene Sosin (“Sparks of Liberty: An Insider’s Memoir of Radio Liberty”), James Critchlow (“Radio Liberty: Hole-in-the-Head”), and J.F. Brown (“Radio Free Europe: An Insider’s View”).

Learn more about the impact of RFE and RL broadcasts on the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe in A. Ross Johnson and R. Eugene Parta’s “Cold War Broadcasting: Impact on the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe.”

Gene Parta takes a close look at the Radio Liberty research effort he helped build in “Under The Radar: Tracking Western Radio Listeners in the Soviet Union,” and drills into the data in “Discovering the Hidden Listener: An Empirical Assessment of Radio Liberty and Western Broadcasting to the USSR during the Cold War.”

RFE and RL reporters faced many dangers on the journalistic front lines of the Cold War – from attempted poisonings, to esoteric murder plots and the bombing of RFE/RL headquarters Munich in 1981 – as described in Richard Cummings’ “Cold War Radio: The Dangerous History Of American Broadcasting In Europe, 1950-1989”

For an in-depth look at jamming and the extensive efforts by the U.S.S.R. to disrupt RFE/RL radio broadcasts, watch “Empire of Noise,” a video documentary by Rimantas Pleikys.

Support Independent Journalism

Join us in advocating for press freedom and supporting RFE/RL journalists who have been unjustly imprisoned.